The icon of St. George on his horseback with his spear fighting the dragon, to save the princess is one of the most famous stories in the Eastern and Western churches. In the Coptic church in Egypt, he’s the prince of the martyrs, the Coptic and Catholic churches celebrate his memory each year at November 16. Many Eastern and Western countries take him as a national symbol. But had really St. George really existed? What’s the origin of his story? This paper will argue that there’s no enough historical evidence to proof the story of St. George, but there is a real history in some parts of the story that goes back to the third or fourth century AD.

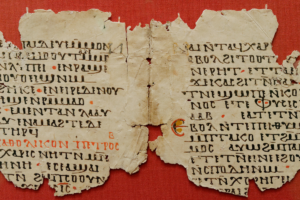

The oldest account of the story we have about St. George goes back to a Vienna manuscript in the mid-fifth century written on Greek which later translated into Syriac.[1] We don’t have any enough primary recourses about his life and martyrdom, but we find many versions of the story that developed later after the fifth century, but nothing before that date. Eusebius of Caesarea mentioned in his works that there was a man who died of persecution at April 23, 303, but he didn’t mention his name.[2]

According to Michael Collins, the story in brief is about George who was born in Cappadocia. His father was a wealthy Christian Palestinian. After his parents’ death, George traveled to Nicomedia to join Diocletian’s army. In 303 Diocletian started to persecute the Christians soldiers in his army, closed the churches, and on February 23, 303, he destroyed the cathedral of Nicomedia. St. George refused to sacrifice to the pagan gods. After the emperor failed to persuade him. The emperor had him tortured, and he lost his life.

The earliest stories about St. George which present details of his martyrdom and his courage in defying the emperor, show that he refused to deny his Christian faith. There was no mention of St. George fighting the dragon. The dragon was later added to the story. St. George killing the dragon was first appeare in the Latin version of Legenda Aurea, which was translated in 1483 by Caxton in the Golden Legend. There was another version that Caxton consulted, which was wrote by Jehan de Vignay, called the Legende Doreo and it was a French translation which started in 1333. All the versions Caxton worked on shared the same story of St. George the knight on his horse who defeated the dragon and saved the princess.[3] The Crusades helped to revive the story of St. George. In 1222 the Council of Oxford established the feast St. George’s day, England regarded St. George as the county’s patron saint. Later the medieval church contributed to the development of Saint George’s appearance to be a soldier from the Crusades bearing a red cross.[4]

The dragon is a mythical creature that was introduced in many stories in ancient literatures. In fact, the dragon slayer motif is one of major themes in many stories. In Greek mythology, Apollo slayed the dragon Typhon. In Mesopotamian civilization, the goddess Inanna slayed the dragon Kur. In Egyptian mythology, the solar god, Horus, stabbed a crocodile, which is a symbol of the dragon. The dragon symbolizes evil and chaos in most of stories, and a fight with the dragon is a fight against the devil. The dragon image appeared in different biblical books like Genesis and Revelation, which symbolizes the devil who was defeated by Jesus Christ. Although dragons are mythical beings, this is not an evidence that the whole story of St. George is legendary. The dragon in the story of St. George should be understood in a symbolical way. Maybe it a symbol for the devil himself, or the emperor who persecuted Christians.[5]

This led us to ask when exactly the connection happened between the story of St. George’s martyrdom and his fight with the dragon? Giles Morgan argues about the origin of the fight with the dragon in St. George’s story. He said, “His legendary conflict with a fearsome dragon. His fabled encounter with this terrifying beast is a later addition to the cult of St George and an episode in the life of the saint that was popularised particularly by the Dominican Prior Jacobus de Voragine.”[6] We can attribute the credit of the fight with the dragon to Jacobus de Voragine’s book “Legenda Aurea” or “The Golden Legend”. This book is a collection of the lives of the saints. One of the books’ stories is the death of St. George as a Christian martyr which starting with the dragon fight.[7]

Jacobus de Voragine’s version of the story is about George who was in the Roman army from Cappadocia. One day he came to a city in Libya. This city was threatened by a dragon living near to a large lake. The citizens can’t overcome on the dragon, they had to feed him two sheep a day to stop the dragon’s anger upon them. They had to make their children sacrifices to the dragon, to the point that only human sacrifice remained is the king’s daughter. The king was very sad that he had to sacrifice his daughter, and he will never see his daughter’s getting marry in life. St. Gorge while he was travelling, he saw the princess crying. The princess explained to him what’s happening. He decided to fight the dragon, defeating him, and saved the princess. St. George said to the people, “You have nothing to fear! The Lord has sent me to deliver you from the trouble this dragon has caused you. Believe in Christ and be baptized every one of you.”[8] This version shows to us how the fight with the dragon was included to St. George’s story to show his courage and faith. The story here is a product of popular theology that developed over time. The same version is used in many stories of St. George with some modifications to the story which Jacobus de Voragine told in his book. These modifications were added to the original story to suit the background of the country or church which will be presented in.

We can focus on the origin of the story in two versions. The first version in a Vienna manuscript which we discussed in the beginning. The second version is the edited version of St. George with the dragon fight which we mentioned above. Despite many other stories of St. George, we could consider that these two versions are the basis for any story about St. George.

The life of St. George it self is still a mystery. There’re many arguments about the historical existence of St. George but without any conclusive evidence to prove or disapprove it. Giles Morgan sees that it’s accepted from many historians and writers that a real St. George did exist.[9] I agree with him that there was a real historical character behind the story.

What we’re sure of that George or maybe another person lived around the third or fourth century AD. According to the Vienna manuscript, which is the oldest story account about St. George we could have, George was a Christian who refused to make sacrifices to the pagan gods. He was tortured and lost his life because his rejection of the pagan worship.[10] This story is very logical in the period which it was written in and is similar to many martyrs’ stories at the beginning history of the church. But like most stories of martyrs, it was modified over time, and “The changes of detail are at times so bewildering that some have argued that the figure of St. George never actually existed at all.”[11] Many stories, its origin including a part of the truth. St. George’s story contains many facts about one of the faithful martyrs who gave his life and refused to deny his faith, and he was a real Christian martyr.

Like any story especially when it’s popular among the people, everyone wants to add their own touch to the story, and to become unique on their own cultural perspective. Like the story of St. George, many countries used the story by the way they preferred. For example, During the crusade, England took St. George story from the east and they saw in him a brave soldier. The story had converted from St. George to an English national symbol of the crusade soldier with his red cross. Others used the famous picture of the dragon slayer to embody the conflict with evil. Many icons had drawn the story of St. George form different countries and churches, these icons are showing many rich Christians symbols and spiritual meanings.

Finally, we do not have any historical conclusive evidence to prove the origin of St. George’s story. But we can assume that there was one of the Christian martyrs who lived in the third or fourth century AD, and later St. George’s story is associated with him to honor his faith. The story of St. George and the dragon came in many versions that is different from the original story. It’s a result of a long history of editing influenced by the mythical image of the dragon. The story symbolizes the courage of the Christian faith, the struggle with evil, and paganism at the time of persecution. The popular theology helped to flourish and spread the story of St. George everywhere. The story of St. George become one of the famous Christians figures among the history of martyrs. The mythical story of St. George and the dragon is still one of the most beautiful icons which inspiring many of people.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alan Brown, David. “Saint George in Raphael’s Washington Painting.” Studies in the History of Art 17 (1986): 37-44, www.jstor.org/stable/42617990 (accessed December 17, 2019).

Baghos, Mario. On the Historical Existence of Saint George. https://www.academia.edu/39133340/On_the_Historical_Existence_of_Saint_George (accessed December 17, 2019).

Brown, Patricia. The role and symbolism of the dragon in vernacular saints’ legends 1200-1500. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Birmingham: University of Birmingham, 1998.

Collins, Michael. St George and the Dragons: The Making of English Identity. Fonthill Media, 2018. https://books.google.com.eg/books?id=Z95VDwAAQBAJ (accessed December 17, 2019).

De Voragine, Jacobus. The Golden Legend: Readings on the saints. Translated by William Granger Ryan. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2012.

Morgan, Giles. St. George: The Pocket Essential Guide. Chichester: Pocket Essentials, 2007.

[1] Michael Collins, St George and the Dragons: The Making of English Identity (Fonthill Media, 2018), Ch. 3, https://books.google.com.eg/books?id=Z95VDwAAQBAJ (accessed December 17, 2019).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Patricia Brown, the role and symbolism of the dragon in vernacular saints’ legends 1200-1500, a thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Birmingham: University of Birmingham, 1998), 114.

[4] Ibid., 62.

[5] Mario Baghos, On the Historical Existence of Saint George, https://www.academia.edu/39133340/On_the_Historical_Existence_of_Saint_George (accessed December 17, 2019).

[6] Giles Morgan, St. George: The Pocket Essential Guide (Chichester: Pocket Essentials, 2007), 45.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend: Readings on the saints, trans. William Granger Ryan (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2012), 239.

[9] Morgan, St. George: The Pocket Essential Guide, 13.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.