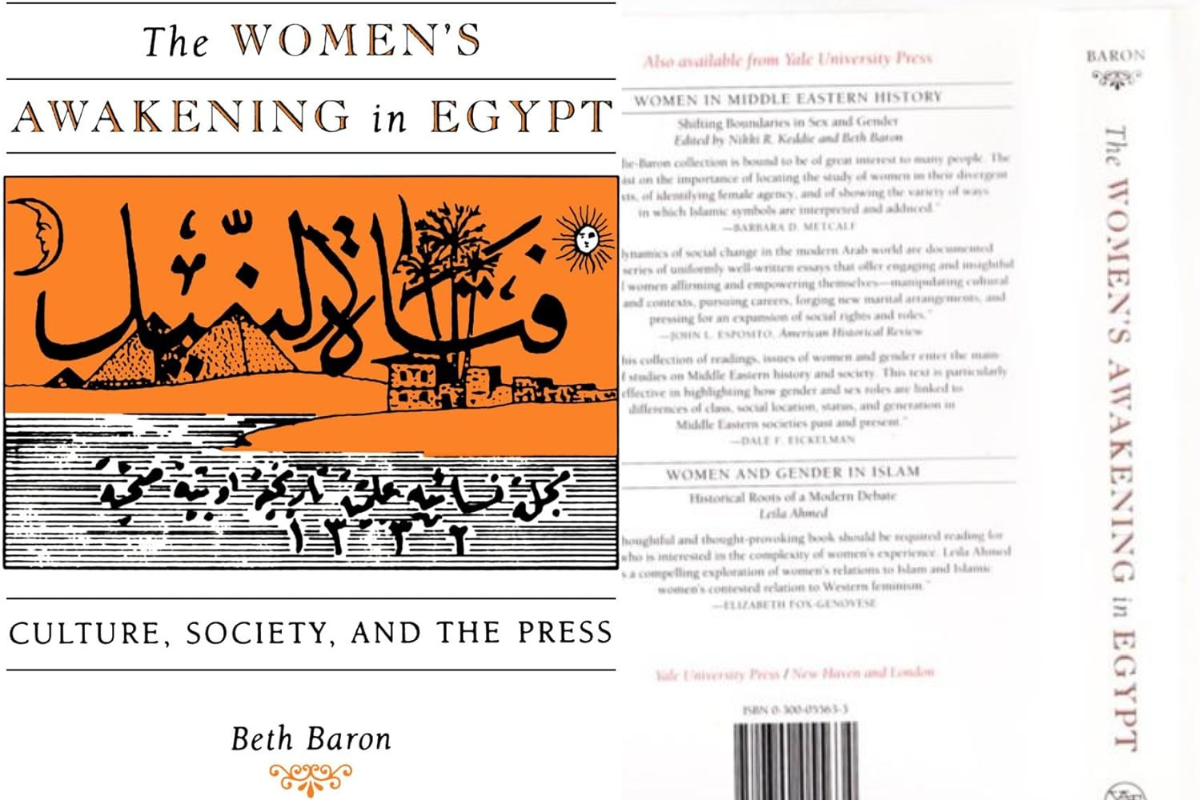

Beth Baron, The Women’s Awakening in Egypt: Culture, Society, and the Press (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994), pp. 259.

Beth Baron’s book, “The Women’s Awakening in Egypt” deals with the role of Egyptian women in the women’s awakening movement during the period 1892-1919. Barron focuses on the first emergence of Egyptian women’s magazines during the period before World War I and ending with the revolution of 1919. Baron argues that the Egyptian Arab women played an important role and contributed to the women’s world awakening movement in the defense of women’s rights. Barron rejects the prevailing notion that gives all the privilege to some feminist men like Qasim Amin and feminists as Malik Hifni Nasif for women’s rights movement in the Egyptian society. Baron sees that there were many intellectual women behind the women’s awakening (al-nahda al-nisa’iyya) and the main tools they used in that period were the women’s journals. Egyptian women started to fight in theses journals for their concerning issues like education, work, family, and their national role.

Baron started her introduction with the first Arabic women’s journal in the Middle East which called al-Fatah (The young woman). It was a monthly journal appeared in Alexandria, Egypt, in November 1892, its editor Hind Nawfal called it the “first of its kind under the Eastern sky” (p. 1). Al-Fatah journals leaded later to many women’s journals which came to be known as al-majallat al-nisa’iyya (women’s journals). With the advent of 1919, there were dozens of these journals that were published throughout the Arab world. Baron sees that Arabic women’s journals give us an opportunity to see a long history of women’s contributions to the women’s awakening who leaded the women’s movement in Egypt. The term “al-nahda al-nisa’iyya” (the women’s awakening) which developed throughout the women’s press and the “female intellectuals used this term to describe the literary movement that they led” (p. 3). I noticed that Baron preferred to call this period with “the women’s awakening” not feminist movement, and I think the reason for that is the term “feminist” was developed and being used in the west world, but the “women’s awakening” term described more the women’s movement as it was known in Egypt and the Middle East. Baron finds that the term “feminism” from nineteenth-century in France, but the term “nisa’iyya” (women) was used in the Arabic language. Despite the both terms have the same meaning of feminism, but Baron sees that in pre-1919 Egypt “this new meaning was not widespread, especially as Egyptian women’s advocates generally tried to distance themselves from Western suffragettes and activists in this period” (p. 6).

Scholars point to Rifa’a al-Tahtawi as one of the earliest modern Egyptian writers to consider the situation of women, and to Qasim Amin who is a famous public figure and reformer in this period. Many considered that Qasim Amin was the first feminists, most of Egyptians until today called him “liberator of woman” or “the father of Arab feminism” and he had many contributions to advocate Women’s rights. But Barron confirms that giving the privilege historically to some men for the women’s awakening movement is the reason behind ignoring many of important female characters and writers rule that contributed to the women’s awakening. Even Baron in last sentence of her conclusion of this book confirms that many women struggled for their rights and it’s a myth—as Baron described—that men only struggled for women’s rights (p. 193). Baron said, “Preoccupation with Qasim Amin and his cohort has led to a misconception that women were not actively engaged in the debate on women’s role in society” (p. 5).

Barron classified women’s rights defenders into three groups: secularist, modernist, and Islamist. The secularists, who concentrated on developing language and education, which were not controversial issues. The modernists used the religious interpretations to improve the state of women in the family. The Islamists were against secularists and modernists, they saw that woman’s rights had given to women in Islam. Baron sees that many of the earliest women writers in Egypt were Syrian Christians. She said, “The Syrian immigrants provided a forum for Egyptians of Turkish background, Copts, and others, who soon started their own publications. The founders of the women’s press were an ethnically and religiously” (p. 7).

The book is divided into two parts or halves. The first part of The Women’s Awakening in Egypt, titled “From Production to Consumption,” it focuses on the female writers who pioneered the Arabic women’s press, their lives, literary output, and the beginning of press (p. 8, 9). This section focuses on the obstacles that women faced in writing for journals. Most of theses issues was about women’s freedom restriction in the Egyptian society, other reasons related to national politics, which Britain was trying to suppress, although these women’s journals did not concern in politics more than situation of the Egyptian woman (p. 37). It’s very interesting to see that many women chose to hide their identities when they started to write (p. 43). They used pseudonyms instead of their real names, this show us that journalism wasn’t a highly regarded profession for women, and they would face rejection in the press syndicate, if they wrote in their real names. Because journalism was a profession practiced only by men. Like Malak Hifni Nasif, she took the pen name “Bahithat al-Badiya” (searcher of the desert) to hide her identity (p. 46). We could see how it was difficult for many women in their beginning of women’s journalism. In the third chapter, Baron wrote about the stages of printing, and all the economic problems related to it. In chapter four, Baron seek to the character of the reader, and his response. The second part of The Women’s Awakening in Egypt, “Texts and Social Contexts,” it sets texts in their social contexts, and show the relationship between these journals and some women’s issues in Egypt. Most of these issues in women’s journals, Baron argued about were woman’s right for education, work, woman’s role in the family, divorce, marriage, and women’s participation in society.

Baron argued that “foreign missionaries” and their schools had a vital role in developing women’s journals and most of the editors came from the missionaries’ schools (P. 133- 137). She tried to relate what the missionaries did, to demonstrate the influence of the West on these journals. I see that Women’s Suffrage in the west is very different than what Egyptian women tried to express in their journals. Maybe what missionaries did was taking care about girls’ education that helped the Egyptian society to realize the importance of girls’ education that later contributed the women’s awakening.

The women’s awakening (al-nanda al-nisa’iyya) phrase appeared through the women’s press. Baron in her conclusion said, “The women’s awakening achieved many of its goals and set precedents and foundations for later female activism not only in Egypt but throughout the Arab world.” (p. 188). I agree with Baron that women’s awakening had a great influence in this period not just in Egypt, but also in the whole Middle East. But we must agree that woman’s awakening happened only between intellectual women in the upper-classes and some middle-classes in a country with high levels of female illiteracy. Baron argued about that in her question, “Was the women’s awakening confined only to the middle classes? Or was it an awakening of wider segments of Egyptian society?” Baron sees that, “Some of the programs that these women championed quickly reached beyond the middle classes” (p. 191). I partly agree with her, maybe there was a little impact on women’s education, but without a clear impact on other sides.

I see that Baron gave us a good book in an important part about the history of feminism movement by Egyptian women. And in this period, which historians ignore many women, like Hind Nawfal, Sarah al-Mihiyya, Fatima Rashid, Malaita Sad, Labiba Hashim, and many other women who played a vital role in this awakening. Baron succeeded in unveiling these women, in a period which historically gives all the privilege to men only. Baron’s book helped us to see the Egyptian and Arab women played an active role as journalists expressing their rights and changing the society.