Introduction

There is no doubt that one of the most significant conflicts in the Church’s history is the Christological controversy that culminated in the fifth century. This controversy is forever linked to the names Cyril of Alexandria and Nestorius of Constantinople. Shortly after being elected as Patriarch of Constantinople in 428, Nestorius opened the door to this great controversy when he refused to call the Virgin Mary Theotokos (Mother of God). The central part of the conflict between Cyril and Nestorius was about the two natures of Christ, and this appeared in the Mariology controversy took the largest share of their disputes in the Fifth-Century Christological controversy. So, this paper will focus on the Christological controversy through the Marian controversy as an example and tries to answer many questions like Was Nestorius a heretic? Was he the main reason for the Christological controversy and the division of the Church in the fifth century? How did the political conflict between the Church of Alexandria and Antioch play the leading role in this controversy? This paper will argue that the main reason for the Christological controversy was the historical background of the political conflicts between the two churches through looking at the background of the early life of the two bishops and the controversies over the term Theotokos that led the events to the Council of Ephesus in A.D. 431. 2

The Early Life of the Two Bishops

First, we need to shed light on the lives of Cyril of Alexandria (c.378–444) and Nestorius of Constantinople (c.381–c.451) before touching on the conflict between them. This background is essential because it shows the basis for the Christological controversy.

- Cyril of Alexandria

Cyril was born in 378 A.D. at Theodosion, Lower Egypt.1 There are not many details about Cyril’s paternal family. Theophilus, the patriarch of Alexandria, was a brother to Cyril’s mother.2 He succeeded his uncle Theophilus and became the patriarch of Alexandria in A.D. 412 after a disturbance between Cyril’s supporters and the followers of his competitor Timotheus. He had ruled the Alexandrian Church for a total of fifty-nine years.3 Cyril followed the policy of his uncle Theophilus, who greatly influenced Cyril’s life in his upbringing, his ordination, and the way he ruled the Alexandria church. Norman Russell said: “Cyril and his uncle Theophilus belong to the new era inaugurated by Theodosius I’s laws against polytheism, an era characterized by Christian violence not only towards pagans and Jews but also towards dissident fellow-believers.”4 Others tried to connect Cyril to the death of Hypatia, the pagan teacher who was killed by a mob, but there is not enough evidence to support this claim.5 Cyril gained power from these violent practices against pagans and Jews, making him a violent trend for everyone who differs from him.

1 Norman Russell, Cyril of Alexandria (London: Routledge, 2000), 4.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid, 3.

5 Robert Benedetto, and James O. Duke, The New Westminster Dictionary of Church History, The Westminster dictionary of church history, vol. 1 (Louisville, Ky: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008), 186.

Cyril is considered one of the controversial figures among historians. There are many opinions about him. For example, many historians see him as the defender and protector of the faith, knight of Orthodoxy, and the church doctor. Other historians like Russell describe him as a 3

“villain”6 and tell a story about people talking after his death that they need “to place a very big and heavy stone on his grave to stop him coming back here.”7 Also, Henry Chadwick describes him as “an acute theologian and a determined zealot in church politics.”

6 Russell, Cyril of Alexandria, 3.

7 Ibid.

8 John Anthony McGuckin, The SCM Press A-Z of patristic theology (London: SCM Press, 2005), 93.

9 Hubertus R. Drobner, Siegfried S. Schatzmann, and William Harmless, The Fathers of the Church: A Comprehensive Introduction (Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic, 2016), 461.

10 The Student’s Companion to the Theologians, ed. Ian S. Markham (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2013), 73.

11 Ibid, The Fathers of the Church, 461.

12 John Anthony McGuckin, St. Cyril of Alexandria: the Christological controversy: its history, theology, and texts (Leiden, New York: E.J. Brill, 1994), 20.

13 Russell, Cyril of Alexandria, 32.

On the other hand, Cyril is considered a great theologian. His writings show that he was a masterful theologian, organized his ideas, and carefully selected his words with linguistic depth. For example, John McGuckin describes him as “one of the most important theologians on the person of Christ in all Greek Christian writings.”8 Based on what was mentioned above, it is essential to look at the Christological controversy from understanding Cyril’s life and character.

- Nestorius of Constantinople

Little is known about Nestorius and his writings. Nestorius was born in A.D. 381 in Germanica in Syria. He was a student of Theodore of Mopsuestia who was the bishop of Mopsuestia (North of Antioch) from A.D. 392 to 4289 Nestorius lived in Antioch as a monk and priest, he gained his reputation for his sermons, and “he was ably trained in the logical, rhetorical school of Antioch.”10 He was elected in A.D. 428 to be the bishop of Constantinople.11 McGuckin argues that Nestorius owed his appointment to the personal recommendation of his childhood friend John, bishop of Antioch. He was also a close friend of Bishop Theodoret of Cyrrhus.12 Russell sees that “Nestorius’ actions were not very different from those of Cyril.”13 However, the main difference is that he was a weak politician, not like Cyril, and sometimes he was described as ruthless like Cyril. 4

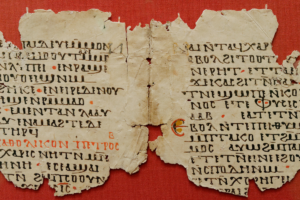

Nevertheless, McGuckin describes him as “no less dogmatic, uncompromising, and ready to use the full extent of his powers, both political and canonical, than Cyril or any of the other leading hierarchs of the period.”14 Little is known about Nestorius’s writings. However, what made us agree with McGuckin is that one of the newly discovered manuscripts on Nestorius’s life, written by himself, is the Persian manuscript the Bazaar of Heracleides. Nestorius told Emperor Theodosius that he pledged to eliminate all heretics, such as the Arians and others. He addressed the following famous words to the emperor, “Sire, give me your empire purged of heretics, and I will give you the kingdom of Heaven. Give me power over the heretics, and I, I will subjugate the Persians who make war on you.”15 This is what Nestorius did later. He started this war and practiced violence against heretics, Macedonians, and Quartodecimans.16

14 McGuckin, St. Cyril of Alexandria, 21.

15 Nestorius, The Bazaar of Heracleides, ed. G. R. Driver, and Leonard Hodgson, (London: The Clarendon Press, 1925).

16 Russell, Cyril of Alexandria, 31.

17 Ibid., 32.

We see that there are many similarities between Cyril and Nestorius. Both had the authority and were powerful men, except Cyril was a better politician than Nestorius. We agree with what Russell said, “What marks him off from his Alexandrian colleague is his much weaker political acumen.”17 They were good theologians and thinkers, and each one of them represented his theological school, and they were faithful to it. So, it is not surprising to see that the Christological controversy intensified in this way between them, and this theological conflict continued for a long time. One of the main reasons for this was the background of their lives and characters.

- The Christological Controversy

- Nestorius’s Rejection of Theotokos

The dispute about the term “Theotokos” (Θεοτοκος) takes the largest share in the Christological Controversy between Cyril and Nestorius. This term became the most prominent dispute in the church history, when Nestorius the bishop of Constantinople, in his sermons, rejected using the term Theotokos. Nestorius started when a delegation came to him to ask what he thought on a disputed theological question. Should the blessed Mary be called Theotokos, “she who gave birth to God,” or Anthropotokos, “she who gave birth to man”?18 According to Russell, Nestorius ruled that neither was wrong, but the expression Christotokos was much better because it was closer to the language of the New Testament.19 Nestorius did not consider either of the terms completely wrong or heretical. However, he gave his term Christotokos through his understanding of the nature of Christ. Gerald Bray argues that Nestorius did not reject the term Theotokos. However, he wanted to use it when accompanied by the term Anthropotokos to reflect the humanity of Christ.20 Or to use the term Christotokos which Nestorius saw it a biblical term and a good compromise and appropriate way to describe the nature of Christ

18 Russell, Cyril of Alexandria, 33.

19 Ibid.

20 Gerald Bray, Creeds, Councils, and Christ (Leicester, England: Inter-Varsity Press, 1984), 155.

21 Russell, Cyril of Alexandria, 33.

First, A priest called Anastasius, who was a member of the entourage Nestorius had brought with him from Antioch, preached a sermon in the Great Church in which he rejected the term Theotokos: “Let no one call Mary Theotokos, for Mary was only a human being, and it is impossible that God should be born from a human being.”21 Then Nestorius began many lectures to correct the theological mistakes included in the term Theotokos and against its use. Nestorius said, “That God passed through from the Virgin Christotokos I am taught by the divine Scriptures, but that God was born from her I have not been taught anywhere. Those who call Mary Theotokos 6

are heretics.”22 Nestorius’ words were a great shock to many; Russell describes it, “If Anastasius’ sermon had caused a sensation, Nestorius’ lectures came as a bombshell.”23 A lawyer called Eusebius accused Nestorius and his party of teaching the adoptionism of Paul of Samosata.24 Nestorius’ lectures caused many disturbances and a local dispute in Constantinople between the newly elected bishop and a set of clerics, monks, and royal family members.25

22 Russell, Cyril of Alexandria, 34.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid., 35.

25 The Student’s Companion to the Theologians, 48.

26 Ibid., 54.

27 R. Drobner, The Fathers of the Church, 461.

At the beginning of his rule in Constantinople, Nestorius was faced with a strong disagreement between different parties in Constantinople: Was it was proper to call the Virgin Mary Theotokos (God-bearer) or Anthropotokos (man-bearer)?26 We see Nestorius was clear from the beginning not to make any heretic judgment about both terms, but he gave his terminology Christotokos (Christ-bearer). He was trying to forge his understanding of the nature of Christ in his own words, not because he was Apollinarian or Adoptionist. Even the differentiation between the divine and human nature of Christ in Nestorius thought was not theologically wrong. Hubertus R. Drobner sees that what Nestorius taught was “theologically entirely correct.”27 We see that the central struggle of Nestorius in the Christological controversy lay in the unpopularity of his term Christotokos in front of Cyril’s term Theotokos, and that is why Nestorius was criticized.

- Cyril’s defense of Theotokos

After Nestorius declared his refusal to use the term Theotokos, Cyril soon learned about the conflict in Constantinople. However, how did Nestorius’ sermons so quickly reach Cyril that made him politically involved in this matter? Susan Wessel argues that “Several Nestorius’ sermons 7

were brought into Egypt, perhaps by Cyril’s detractors.”28 Immediately, Cyril began mobilizing strong opposition to get support against Nestorius. First, he wrote to the monks and priests of Egypt. Later the monastic support played an essential role in the events at Ephesus.29 Cyril declared to them that “if Mary is not Theotokos, as Nestorius’ sermons claimed, then Christ is not God.”30 Cyril succeeded in making the monks on his side. Even some of the monks, who were influenced by Nestorius’ thoughts, Cyril persuaded them. One of Cyril’s strong arguments to defend Theotokos is that Athanasius himself used this term while he was familiar with all the traditions of the Church Fathers.31 Cyril sought as much as possible to demean Nestorius. We cannot ignore the historical background of the political competition between Alexandria and Constantinople. McGuckin agrees that the “innate rivalry” between Alexandria and Constantinople was an essential factor in the controversy between Cyril of Alexandria and Nestorius.32 Cyril inherited from his uncle this tension between the two churches and the struggle over Who was worthy of leading the Christian world.

28 Susan Wessel, Cyril of Alexandria and the Nestorian controversy: the making of a saint and of a heretic (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 76.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 Ibid., 79.

32 McGuckin, St. Cyril of Alexandria, 12.

33 The Student’s Companion to the Theologians, 48.

Cyril and Nestorius exchanged many letters arguing against each other. They failed to persuade each other, and in some letters, they exchanged sharp words and heresy charges. Both had a mutual appeal to Pope Celestine in Rome, ending with the emperor condemning both in A.D. 430. After that, the emperor Theodosius called for an ecumenical council in the summer of A.D. 431 at Ephesus.33

We can summarize Cyril’s attitude towards Nestorius, the Christological controversy about the nature of Christ, and Theotokos title, in two main theological and political reasons. 8

Firstly, Cyril emphasized the teachings of Athanasius about the one nature of Christ and his famous sentence, “after the union one nature.” However, Nestorius emphasized the human nature of Christ. Michael Parker argues that the dual nature of Christ was the reason for controversy between the two Christian centers, Alexandria, and Antioch. The school of Alexandria, led by Cyril, agreed that Christ was both God and human but focused more on the unity of Jesus as a person. The school of Antioch, led by Nestorius, saw that Alexandria was focusing more on the divine nature of Jesus, neglecting human nature. Antioch decided to believe in the human and divine nature of Christ, but with more focusing on the human nature of Christ.34

34 Michael Parker, A history of the Church, trans. Marian Katkot (Cairo: Dar al-Thaqafah, 2019), 76- 77.

35 Ḥanna Al-Khūḍari, Tārīh̲ al-fikr al-masīḥī: Yasūʻ al-Masi ̣̄ḥ ʻabra al-aǧyal, “History of the Christian Thought.” Vol. II (Cairo: Dar al-Thaqafah, 1986), 204.

36 Al-Khūḍari, 204.

Secondly, Cyril sought to spread his influence and authority in the east from a theological and political point of view.35 The conflict between Alexandria and Constantinople was an ancient and deep one when the second Ecumenical Council was held in Constantinople in A.D. 381. This Council decided to rank Constantinople in the second place after Rome and grant the archbishop of this chair an ecumenical title that made Alexandria jealous because the Church of Alexandria is now in the third place. Besides, bishop Theophilus, Cyril’s uncle, was the trial leader and exiled the Archbishop of Constantinople, John Chrysostom, in A.D. 403.36 We believe that these reasons for a long history of political conflicts between the two churches caused Cyril to take a negative stance against Nestorius.

- Theotokos at the Council of Ephesus

The emperor Theodosius II convened a third ecumenical council held in Ephesus in A.D. 431 to resolve the disagreement between Alexandria and Antioch. However, the Pope of Rome, Celestine, held a local council in A.D. 430 to discuss this conflict. The local Council in Rome relied on many 9

sources that were not objective, including Cyril’s letters about Nestorius. The German Catholic scholar Grillmeier comments about this local synod that “neither the Pope of Rome nor his synod was worthy to judge Nestorius because the information on him was distorted.”37 From the beginning, the judgment of Nestorius was unfair, and the Pope of Rome condemned him even before the events of the Council of Ephesus.

37 Ibid., 219.

38 Parker, A history of the Church, 77.

39 Ibid.

40 Ibid.

The emperor ordered that any decision be prevented before the start of the Council of Ephesus, and any new decision would be taken by majority vote. Complicated events accompanied the Council of Ephesus. Parker writes that “The behavior of this council was a scandal, and it has always been an embarrassment to the church.”38 That is because the first to arrive the Council was Cyril with fifty bishops, and the forty bishops Antioch delegation headed by John the Patriarch of Antioch had been a few days behind the date of the council opening.39 The Pope’s delegates did not arrive at Ephesus, nor the Antioch Bishops, even though they told the Council of their delay, yet Cyril opened the Council in the presence of one hundred fifty-three bishops, despite the protest of sixty-eight bishops, and despite the warning of the representative of the emperor. The latter asked Cyril to wait for the coming of the Eastern Bishops. The Council illegally began its sessions. Cyril wanted to confirm the decisions taken before in Rome and Alexandria local synods. Cyril considered himself the representative of the Pope and the president of the Council. Nestorius was invited three times to appear before the Council to present his teachings, but he refused to attend, saying, “We will speak after the coming of all bishops.” Finally, the Council had issued its ruling condemning Nestorius. When John of Antioch arrived, he declared the Council of Ephesus illegal and held another Council condemning Cyril.40 After that, Emperor Theodosius arrested both Cyril 10

and Nestorius. Cyril succeeded in getting out of jail and returning to Alexandria, but Nestorius submitted the emperor’s decision and accepted being exiled from Constantinople.41

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid, 77-78.

43 Al-Khūḍari, 193

44 Ibid.

Many historians agreed to condemn Nestorius as a heretic for a long time, but these charges were from his enemies’ perspective.42 However, thanks to the discovery of Nestorius’ book “Bazaar of Heracleldes,” it is an evident book that Nestorius was not a heretic. Many scholars like E. Amann, Galtier, Friedrich Loofs, and others confirm that Nestorius never taught any ideas about adoptionism or two Christs.43 Nestorius taught that Christ had two natures united in one-person dyophysitism,44 which is why Cyril thought that Nestorius was teaching about two persons of Christ.

Conclusion

It is dangerous to judge history from only one angle without objectivity. This applies to the Christological controversy when studying it without the historical background and the political conflicts between the Church of Alexandria and Antioch. Although Cyril was a brilliant theologian, sometimes he lived politically malicious and violent, but his manipulation is evident when he led the Council of Ephesus. Cyril succeeded in making a legacy for him among the church fathers. Although Nestorius was trying to understand the nature of Christ, the expressions and ideas that he used were not explicit and used against him. The Christological controversy led to the making of a saint and a heretic. We see that the Church could not find some way to avoid the Christological controversy and the division resulting from it for political reasons. That division of the Church was inevitable, regardless of the Christological controversy between Nestorius and Cyril. 11

Bibliography

Al-Khūḍari, Ḥanna. Tārīh̲ al-fikr al-masīḥī: Yasūʻ al-Masi ̣̄ḥ ʻabra al-aǧyal, “History of the Christian Thought.” Vol. II. Cairo: Dar al-Thaqafah, 1986.

Benedetto, Robert and James O. Duke. The New Westminster Dictionary of Church History. The Westminster dictionary of church history. Vol. 1. Louisville, Ky: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008.

Bray, Gerald. Creeds, Councils, and Christ. Leicester, England: Inter-Varsity Press, 1984.

Chadwick, Henry. The Early Church. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1968.

McGuckin, John Anthony. St. Cyril of Alexandria: the christological controversy: its history, theology, and texts. Leiden, New York: E.J. Brill, 1994.

McGuckin, John Anthony. The SCM Press A-Z of patristic theology. London: SCM Press, 2005.

Nestorius. The Bazaar of Heracleides. Edited by G. R. Driver, and Leonard Hodgson. London: The Clarendon Press, 1925.

Parker, Michael. A history of the Church. Translated by Marian Katkot. Cairo: Dar al-Thaqafah, 2019.

- Drobner, Hubertus Siegfried S. Schatzmann, and William Harmless. The Fathers of the Church: A Comprehensive Introduction. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic, 2016.

Russell, Norman. Cyril of Alexandria. New York: Routledge, 2000.

The Student’s Companion to the Theologians. Edited by Ian S. Markham. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2013.

Wessel, Susan. Cyril of Alexandria and the Nestorian controversy: the making of a saint and of a heretic. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.