Introduction

We need to answer this question, why do we need to see God as an inclusive God? In the world of diversity in which we are living today, it is difficult to consider that others (non-Christians) are apart from God. If we believe that Christ died for everyone, so everyone should be included by God’s love. If God asked us to love each other in Matthew 22:39, how He does not care about others? As a Presbyterian pastor, I believe in the doctrine of unconditional election (the exclusive election of the believers), and to this day I am completely convinced of it through my understanding of the Bible and my reformed theology. The limited atonement doctrine contributed to making God exclusive to his chosen ones before the creation of the world. The Calvinist election model paints an image of God as separate from the non-elected. This shows that his love is only for his believers. That influences our thinking about how God deals with others, furthermore, the Holy Spirit does not work except on the elect, who are attracted by the grace of God. On the other hand, the emergence and development of Karl Barth’s doctrine of election show God deals with all humanity and wants to be in a relationship with Man. Barth’s ideas of the election doctrine succeeded in showing the message and love of Christ can reach everyone. No man is predestined from knowing God, but all are chosen in Christ and they can have a relationship with God. In contrast with the Calvinist understanding that contributed for a long time, God is exclusive to some people only and the non-elected does not have a chance in God’s plan. From this point of view, this paper will argue that Barth’s development of the election doctrine contributed to showing God including everyone in his election through Jesus Christ. The paper will take Barth’s doctrine of election as a good model of inclusivism Christianity without compromising our basic beliefs such as the centrality of Christ’s salvation.

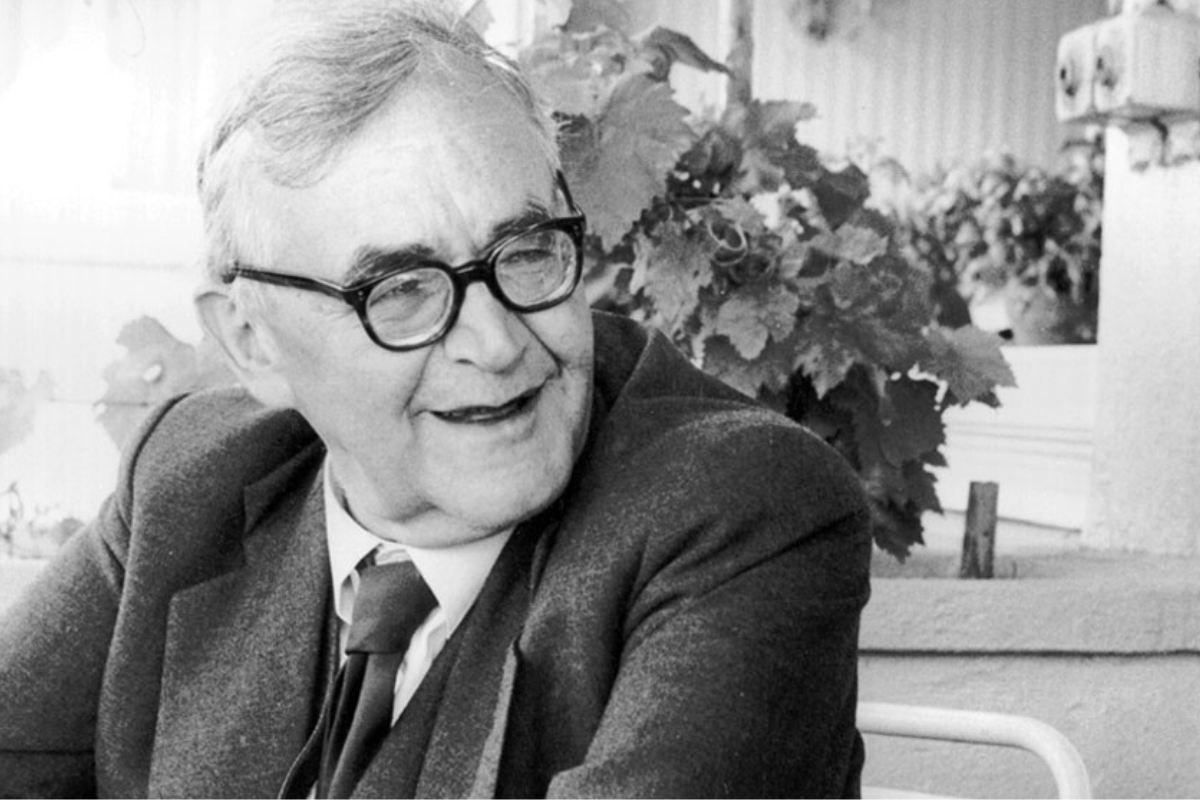

Karl Barth’s Doctrine of Election

Karl Barth is one of the greatest theologians of the twenty-first century. His development of the doctrine of election is considered one of his most important achievements and it occupies a great position among scholars. The doctrine of election occupies a big space in Barth’s main work the Church Dogmatics in more than 500 pages.[1] Bruce McCormack says about it, “I am confident that the greatest contribution of Karl Barth to the development of church doctrine will be located in his doctrine of election.”[2] Emil Brunner was pleased with the doctrine of election because he saw that Barth successfully offered a corrective understanding of Calvin’s teaching and that Barth made Jesus Christ the “eternal, ontic ground for election.”[3] David Gibson considers that “Karl Barth’s doctrine of God’s gracious election in Church Dogmatics II/2 is a monumental achievement.”[4] The doctrine of election plays a fundamental role in our understanding of the nature of the relationship between God and people. We will focus on Barth’s main doctrine of election characteristics that contributed to showing God’s freedom and love to include everyone through Jesus Christ.

The Subject of Election

We understand from the traditional Calvinism that God’s election is for people. Calvin thought that God did not elect everyone to be saved but He elected some people to be saved and others to perish. That is why it is called sometimes double predestination to refer that some people are predestinated to salvation and others for damned. Barth said, “I would have preferred to follow Calvin’s doctrine of predestination much more closely instead of departing from it so radically. … But I could not and cannot do so.”[5] Barth understood God’s election in a different way than Calvin. Barth saw that Jesus Christ was “the subject and object” of God’s Election from the beginning.[6] He is the electing God and the elect human at the same time. We could consider this the main cornerstone for Barth’s election. The election is not for individuals, but it is for Jesus Christ himself. Barth gives a correction of traditional Calvinism about double predestination in his exegesis on Paul’s letter to the Ephesians that the apostle Paul “is concerned about the double predestination of the human creature in God, not about the double predestination of the human creature.”[7] So the election is for humanity in Jesus Christ, not the people themselves as individuals. God’s grace is not in the election of individuals, but it is in the election of Jesus Christ, he is “the divine election of grace.”[8] The election is God’s decision to be with us not against us or condemn us.

Modern Calvinism attempted to solve this dilemma that some humans were predestined to damnation, and God still loves them by saying that people who are predestined are only the elect for salvation not for perdition. Barth solved this problem by considering each person has the chance to be included in God’s election through Jesus Christ. God elects Christ for salvation, so any person in Christ will be saved and share Jesus’ election. We can see God as an inclusive God to all humanity when “Jesus Christ as God and humans stand between them as mediator: in Him, God reveals Himself to humanity and humanity knows God in Him.”[9] We do not need to look at God that he divided humanity into two teams, one is saved, and the other has perished. Barth’s election “refers not to a decision of God in which the human race is divided into the elect and the reprobate, but to God’s self‐election and the election of humanity, both actual in Jesus Christ.”[10] If God elected individuals to salvation, he will be an exclusive God for the elected and all those outside his election do not have the ability or chance to know him. They are all condemned to eternal punishment. This brings us to the next point by which Barth thought about eternal punishment.

The Eternal Punishment

We want to look at others not with the eyes that they are eternally condemned, especially non-Christians in our society. The election determined the love and mercy of Jesus Christ to all humanity and the judgment at the same time. This means that Jesus Christ is the act of love and judgment (reprobation).[11] This happened in the incarnation of Jesus and the reprobation[12] when he experienced and subjected himself to death physically on the cross and spiritually when the Father abandoned him.[13] For Brath, “Jesus Christ is the only reprobate.”[14] The rejection was for Jesus Christ not for humanity. There is no person predestinated in himself for eternal punishment. As we see in Christ the same image of two opposites, which is acceptance and rejection at the same time. We could see it also in Barth’s idea of community election including Israel and the church. Israel reminds us of the Jews who refused to be included in the election and to believe in God’s promises to them. And the church reminds us of God’s grace. In God’s one community, there is grace and judgment included in his election of Jesus Christ.[15] Barth saw the election as God’s move to all humanity so everyone who decided to follow Jesus has the chance to be included in God’s election. When Barth was asked,[16] “Do you believe in hell?” He replied, “No, I don’t believe in hell; I believe in Jesus Christ.”[17] Instead of our focus on the eternal punishment of others, we need to look at them through the love of Jesus Christ, and everyone has a chance in some way to know God. The grace of God did not close the door for some people to perish and others to be saved but to let everyone decide if they will accept their election in Jesus Christ or they will not. God calls humanity to believe in his election in Jesus Christ. Those who will believe in “their election and disbelieve in their rejection.”[18]

God’s Gracious Election

Although Calvin’s and Barth’s thoughts about the election are based on the grace of God, each one of them saw God’s grace in the election in a different way. Calvin saw the grace of God in His election to the chosen to be saved. The whole world was sentenced to death and cannot know God because of sin. That is why God in His grace and mercy chooses to save the elects because without election no one will be saved. For Barth, the covenant of grace is “an act of Self-determination by means of which God determines to be God, from everlasting to everlasting, in a covenantal relationship with human beings and to be God in no other way.”[19] Barth sees God’s covenant relationship with humanity is inevitable because He is God. God in His love chooses to be with Man not against him. In His freedom, He decided that grace to be with men and the judgment to be in Jesus Christ.[20] The election is the best expression to say God is for man. We need to see God’s dealings not only with us as elects (Christians) but also includes every person who is important to him. In the same way, God elected the human Jesus Christ to represent all humanity, He can also help and reach them to believe and accept their included election in Jesus Christ.

Distinguish from Universalism

Anyone does not need to be a universalist so could adopt Barth’s election. Barth has been accused so often that his ideas are a form of universalism because his teaching of God’s gracious election in Jesus Christ and the doctrine of election may imply it. Many scholars see it differently, Joseph Bettis says that “for Barth, one can reject both Arminianism and double predestination without having to accept universalism.”[21] But Hans Urs von Balthasar says that “it is clear from Barth’s presentation of the doctrine of election that universal salvation is not only possible but inevitable. The only definitive reality is grace, and any condemnatory judgment has to be merely provisional.”[22] We need to distinguish between Barth’s election and universalism by defining it first.

Universalism has many ideas that sometimes differ from one another, but they agree with the main idea that everyone will eventually be saved. Universalism in its simple definition is “the teaching that every person to live on planet Earth will ultimately be eternally saved.”[23] David Harts shares the same definition when he describes the Christian universalist saying, “Christians, that is, who believe that in the end all persons will be saved and joined to God in Christ- since the earliest centuries of the faith.”[24]

Despite Barth’s refusal of the limited atonement and he saw that all humanity is saved and chosen in Jesus Christ, the ideas of universalism that we displayed above do not match identically with Barth’s thoughts. Barth commented clearly on his opinion about universalism and said, “I don’t teach it [universalism], but I also don’t teach it.”[25][26] It seems as if Barth did not accept or reject the ideas of universalism. Both Barth’s thoughts of the eternal election of humanity in Christ and most shapes of Christianity universalism affirm the doctrine of salvation (soteriology) due to Christ’s unlimited atonement. For Barth, his universal salvation scope does not go so far from the necessity for individuals to accept their election which included Jesus Christ. Contrary to Christian universalism, which believes that everyone will be saved in Christ, regardless of whether they accepted and knew Christ or not. I think Barth’s doctrine of election is a form of universalism, but it emphasizes the centrality of Christ’s salvation and humanity’s need to accept it.

Conclusion

We could consider that Karl Barth’s contribution to the doctrine of election is a balanced understanding of an inclusive God who wants to be in a relationship with all humanity through Jesus Christ. We do not need to judge God’s relationship with humanity through two extremist looks. From the Calvinism point of view, God elected some people to be saved, or from the Universalism view that considers everyone will be saved regardless of whether he knows God or not. Barth gives a new hope that we can see the loving and merciful God wants to restore the fallen humanity to the true knowledge of him. We need to see others as a possibility to be elected in Jesus Christ who is elected from God to save humanity. We need to develop our theology so that we do not look at others that they are being excluded from God’s plan because they are non-Christians with our traditional concept. At the same time, we do not do this in a way that we compromise our basic beliefs far from the centrality of Jesus Christ in our salvation.

Bibliography

Barth, Karl. Church Dogmatics. Vol. 2. Edited by G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1957.

Bentley Hart, David. That All Shall Be Saved: Heaven, Hell, and Universal Salvation. London: Yale University Press, 2019.

- Crisp, Oliver. “On Barth’s Denial of Universalism.” Themelios 29, no. 1 (Autumn, 2003): 18–29. https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/themelios/issues.

Gibson, David. “Barth on Divine Election,” in The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Karl Barth: Barth and Dogmatics. Vol. I. Edited by George Hunsinger and Keith L. Johnson. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2020.

Greggs, Tom. Barth, Origen, and Universal Salvation: Restoring Particularity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Klooster, Fred. The Significance of Barth’s Theology: An Appraisal with Special Reference to Election and Reconciliation. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1961.

Hindson, Ed and Ergun Mehmet Caner. The Popular Encyclopedia of Apologetics: Surveying the Evidence for the Truth of Christianity, The Ransome Trilogy Series. Eugene, Or: Harvest House Publishers, 2008.

Jüngel, Eberhard. Karl Barth: A Theological Legacy. Translated by Garrett E. Paul. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1986.

McCormack, Bruce. “Grace and Being: The Role of God’s Gracious Election in Karl Barth’s Theological Ontology.” In the Cambridge Companion to Karl Barth. Edited by John Webster. UK: Cambridge Press, 2000.

Morrison, Stephen. “Karl Barth on Universalism.” Https://www.sdmorrison.org/karl-barth-universalism. Accessed January 17, 2021.

- Kantzer, Kenneth. “Do You Believe in Hell?” Christianity Today. February 21, 1986. https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/1986/february-21/from-senior-editors-do-you-believe-in-hell.html.

[1] Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, vol. 2, ed. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1957).

[2] Bruce McCormack, “Grace and Being: The Role of God’s Gracious Election in Karl Barth’s Theological Ontology,” in The Cambridge Companion to Karl Barth, ed. John Webster (UK: Cambridge Press, 2000), 92.

[3] Ibid.

[4] David Gibson, “Barth on Divine Election,” in The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Karl Barth: Barth and Dogmatics, Vol. I, ed. George Hunsinger and Keith L. Johnson (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2020), 47.

[5] Barth, x.

[6] Barth, 102.

[7] Gibson, 48.

[8] Barth, 95.

[9] Tom Greggs, Barth, Origen, and Universal Salvation: Restoring Particularity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 23.

[10] Gibson, 50–51.

[11] McCormack, 98.

[12] In Calvinist doctrine, the reprobate is those Christ rejected before the world began. “Reprobation,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reprobation.

[13] McCormack, 98–99.

[14] Fred H. Klooster, The Significance of Barth’s Theology: An Appraisal with Special Reference to Election and Reconciliation (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1961), 41.

[15] Ibid., 42.

[16] In one of the lectures of Karl Barth in the United States in 1963 at Fuller Seminary.

[17] Kenneth S. Kantzer, “Do You Believe in Hell?,” Christianity Today, February 21, 1986, https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/1986/february-21/from-senior-editors-do-you-believe-in-hell.html

[18] H. Klooster, 43.

[19] McCormack, 98.

[20] H. Klooster, 41.

[21] Oliver D. Crisp, “On Barth’s Denial of Universalism,” Themelios 29, no. 1 (Autumn, 2003): 18–29, https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/themelios/issues.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ed Hindson, and Ergun Mehmet Caner, The Popular Encyclopedia of Apologetics: Surveying the Evidence for the Truth of Christianity, The Ransome Trilogy Series (Eugene, Or: Harvest House Publishers, 2008), 487.

[24] David Bentley Hart, That All Shall Be Saved: Heaven, Hell, and Universal Salvation (London: Yale University Press, 2019), 1.

[25] Stephen Morrison, “Karl Barth on Universalism,” https://www.sdmorrison.org/karl-barth-universalism. (accessed January 17, 2021).

[26] Eberhard Jüngel, Karl Barth: A Theological Legacy, trans. Garrett E. Paul (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1986), 44–45.